I have this friend that, for the first couple of years that I knew him — through Paul, the Mayor of Piety Street — I didn’t ask him where his family was from. He was, as they say, born and raised here. But when I learned his last name, I recognized it, a very common one in Latin America. It was one that must have had an eñe, but in its present form, it was just an n; no virgule. I guess that one got lost in the moving process.

There’s a certain prestige in being a Black man from New Orleans. Even with all the roughness that it includes, or precisely because it includes the complexity of the city’s culture, it makes many choose it as their first demonym, no matter where you came from. But the stories underneath the demonym are still there, weaving the character of the community. The ever-present past of New Orleans gives a distinct character to the way we interact, from those who have rarely been out of the city, to those who realize this is a good place to rest in the epic journey of the migrant.

Hondurans

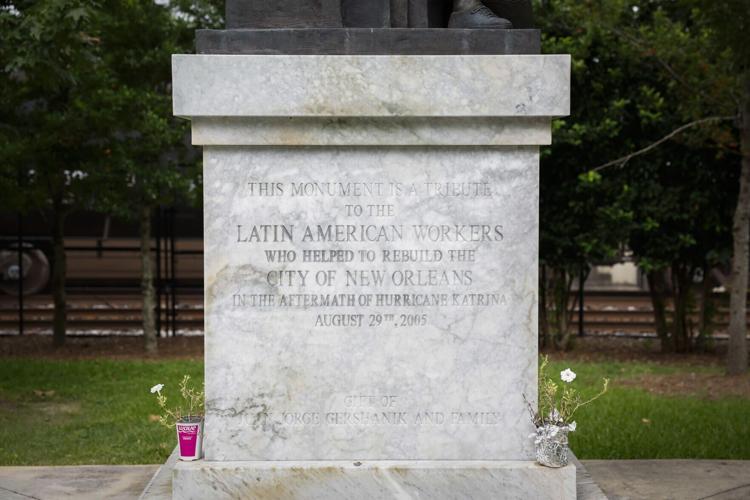

A monument in Crescent Park along the Mississippi River honors the Latin American workers who helped rebuild after Hurricane Katrina, in New Orleans, La., Friday, Aug. 28, 2020. Due to weather concerns, the Prayer Service for Katrina Immigrant Workers event was moved from the Hurricane Katrina Latin American workers monument in Crescent Park to First Grace United Methodist Church. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

Hondurans are everywhere in New Orleans, their food, their handiwork, their intelligence, their cadence. Even other communities from Latin America get cover in their knowledge and networks across the city. It would seem that they don’t reclaim the fair space they deserve after being here for so long.

The monument joggers pass by

Everything is sort of new in Crescent Park. Until a few years ago, there was no park but a horrid border between the river and the Marigny and Bywater neighborhoods. Then the park opened. It’s basically a strip with a couple of leisure spaces made from the old wharf and a warehouse, now used to watch the boats, skate or kiss. Along the path, as if going from the Industrial Canal toward the French Quarter, you can see to your right a monument donated by a local Hispanic entrepreneur that honors the Latin American workers who came to rebuild after Katrina. It states that, on front of the monument, in English, and in Spanish on the back. I wonder if it was on purpose, a way of underscoring that the important part of the job is happening outside of your field of vision, so that it doesn’t bother you.

The monument features two male workers rebuilding a house. On one side, a female worker has a broom. Not that it’s easy to sweep after a hurricane, or that is not important, but I have met the women who came to rebuild the city. These women can sweep, yes, but they can also bring down walls with their own hands and then bring them up, they can paint porches and fix roofs. They came mostly from Honduras, Mexico, El Salvador and Guatemala, and they are some of the strongest, most ferociously ingenious human beings I have met. Talk about firemen running toward the fire when everybody else is running in the opposite direction. They came when the city had been deserted, cleaned it, rebuilt it and saved it. That broom stands for a lot more than sweeping.

The coward who took a pause

I met many of the immigrant workers when I was invited by Julie Norman to do a workshop with Spanish-speaking women at the Family Justice Center. All of them have gone through different versions of hell to get here: escaping a terrible situation at home, surviving a terrible voyage, enduring a terrible American welcome. But they preserved their hopes, good humor and stamina. One day, I asked them to write about a moment of strength. One said that after the months of reconstruction, she started working at a restaurant where the owner routinely stole the tips from the undocumented workers. She complained, and the owner said, “Do you want me to call immigration?” to which she replied, “Go ahead, but I bet I can call the police first and tell them you reuse the paper plates you are supposed to throw away.” The guy said nothing but stopped stealing the tips.

Politics

This one transplant-settler bought a house in the French Quarter and then started harassing a person who had a bubble machine close by, and he called the police multiple times to make them stop. As a response, dozens of people came and threw a bubble party outside his house. Hopefully, he understood. But it’s for things like these that some say New Orleanians are apathetic or disinterested in politics, that they would take anything as long as their right to party is respected. To this, I say:

1. Parties are not a minor part of a civilized society; they are a way of marking time, celebrating life and creating community.

Yuri Herrera

2. People do care. New Orleanians just don’t go through the motions of politics as dictated by mainstream media. But when they participate, it’s powerful. I went to the Black Lives Matter rallies in New Orleans. Before this, I have been to many marches and political meetings of different kinds (including the kind where police charge against people), but never have I felt such a determined, illuminating rage as the one I felt in Duncan Plaza, something like saying: You think you know me? I’ll show you how it’s done. And it was done. We need more of that.

Paul

It was maybe my second week in New Orleans when Paul, Anthony Paul, the Mayor of Piety Street, asked me if I had seen the whole video of the Super Bowl in which the Saints won. I said no, so we watched it, him for the nth time. After that baptism, he introduced me to the city, its lingo, its perils, its holiness; how important the crawfish boil is and how important it is to share it with neighbors.

During Katrina, Paul’s family took refuge in different spots — wife Sonjie and the twins in the Superdome, son Rodnell in the Convention Center, while Paul stayed in Piety guarding the house, armed with a shotgun, steaks and beer. Across the street, in the house where we would later live, was his friend Dave. They would throw whatever the other needed across the flooded street. He survived all that. He was even in an aerial shot by CNN, cooking on the sidewalk when the waters had started receding.

Years later, he was killed by a guest he had welcomed into his house. The suspect spent one year in prison, then, due to some way of the system, was let go.

The most beautiful man on the bus

The public buses are probably the safest place to be in New Orleans. They are clean, drivers are kind and helpful, and in a city where crazy is the norm, on the buses, crazy takes a recess. That’s why this guy on the No. 8 route stood out. A young guy standing by the middle door. There were free seats, but he obviously didn’t want to get wrinkles on him. He was calmly but thoroughly dusting his shirt, his shoulders, his pants, his shoes, again and again. He already was looking good, not elegant, just ready. All the people around were watching him, but he wasn’t aware, so focused was he on what was to come. He got off at the Louis Armstrong Park stop. You could feel a vibe of encouragement coming from the passengers looking at him go, a wave of support so that he could get the job. That was it, even though nobody said anything.

The day of the snowfall

Even if you had seen a snowfall, you have not seen anything like this. Nobody has seen this much snow falling in New Orleans for more than a century. The houses acquired impossible shapes; the city was suddenly soundproofed with white water. It was as miraculous as witnessing a surge of flowers in the middle of the desert.

The iconoclast

That’s why some people come to see nothing but their hands holding the most stupid drinks known to man, because they are afraid to grasp this other way of being, this skepticism toward the “greatness” others accept as a fact, because it is not resilience, it is rebelliousness.

Yuri Herrera is a 9th Ward resident who hails from Mexico. He teaches at Tulane and is author of several books exploring migration, politics and identity. His latest, “Season of the Swamp” is set in 19th-century New Orleans.