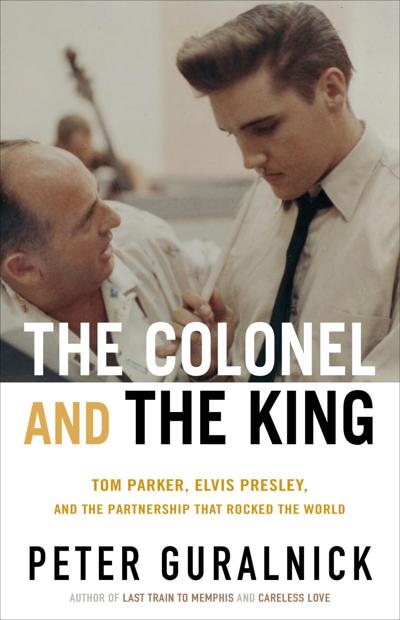

"The Colonel and the King” by Peter Guralnick; Little, Brown and Company; 624 pages

When Colonel Tom Parker approached Sam Phillips in 1955 with a proposal to arrange a recording contract for a little-known, but promising singer named Elvis Presley, Phillips was not only exasperated with the man’s nerve, he was indeed insulted.

Phillips responded with something like, “He records for me, Sun Records, and he’s not for sale!”

Phillips had already released five singles by Presley that had gained some regional success, but it was the fanatical response to Presley’s in-person shows at the Louisiana Hayride and small venues in the area that had so impressed the Colonel.

Never one to give up, ultimately Parker told Phillips to name his price and was told $35,000. Never before had a musician’s contract been sold for such a large sum. But the Colonel had made a deal that Steve Sholes at RCA in Nashville could accept, and in January 1956, RCA introduced their first Presley recording, “Hound Dog,” and thus an entertainer the likes of which the world had never seen was launched. It placed No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100 and also No. 1 on its Country & Western chart, both for months.

With this explanation of how the Presley-Parker relationship began, Parker's personal and professional life story, and it’s a long and amazing one, can begin. As a young teenager, Dreis van Kuijik stowed away on a ship leaving his native Holland and ended up in New Jersey for a new life. Soon after arriving, the future Colonel found an ideal (for him) job with a circus.

He was fortunate to be taken in by a Dutch family in New Jersey, but soon he headed west, spending several months as a hobo working his way to Los Angeles. There, he worked briefly with the Aimee Semple McPherson evangelistic temple, learning some of the tricks of promotion that would serve him well in show business.

Soon, though, he was again on the road, ending up in Huntington, West Virginia, where he was befriended by a family named Parker that allowed him to work with their pony ride concession in a small circus. When he moved on again, he began identifying himself as Tom Parker, contending that the Parker family had adopted him, thus providing him with his new name. Inventing a date of birth in Huntington, he established himself, in time, as an American citizen by registering with Social Security and later serving in the military.

The title of Colonel came much later, bestowed upon him by Louisiana Gov. Jimmie Davis.

Upon receiving a medical discharge from the military (depression according to the Army, a knee injury according to Parker), the future Colonel was again working as an advance man with a circus, next for a tour of then-singing star Gene Austin, and later as head of the Tampa, Florida, Hillsborough County Humane Society. Guralnick provides quotes from newspapers and employers attesting to his impressive performance as a promoter with all three ventures.

Moving to the manager/promoter role for various Grand Ole Opry acts, he had outstanding success in helping Eddy Arnold become the acknowledged No. 1 country act of his day. Parker also launched a successful promotion of another country singer, Hank Snow.

With this background established, Guralnick launches into the story the book’s title promises, “The Colonel and the King.” Guralnick devotes approximately half of this 624-page book to discussing the character of Colonel Parker, especially as related to the shaping of Elvis’ career, and the other half to Parker’s letters and commentary on their context.

The letters tell much about the promoter’s inner as well as professional life, but the most interesting ones are to Presley and his parents. These reveal the role he played as adviser, almost a father figure, always showing concern for his client’s welfare and the importance of good choices in his career as well as his personal and financial life.

Guralnick brings a depth of knowledge of Presley from his previous publication of a two-volume biography of Presley and a biography of Sun Records founder Phillips.

Upon Presley’s release from his Sun contract, the first major effort was the famous “Hound Dog” recording sessions at the Nashville studios of RCA. Next came road bookings and media appearances, for which Colonel had all the right contacts.

The most memorable of Presley's initial introductions to a wide audience is his famous debut on "The Ed Sullivan Show," which set off a national debate about Presley’s animated performance, which many decried as lewd and not suitable for TV.

Presley’s stardom, demonstrated by the near-riots of his fans during his live shows and the resulting deluge of publicity, meant it was time for Hollywood.

His first movie, “Love Me Tender,” was quickly completed and released in 1956. In the same year, Presley made his Las Vegas debut as an add-on to a show by other performers. Movies and recording consumed most of his time until 1968, with a total of 31 movies, most of them less than memorable.

By the time his final film was shot in 1969, Presley was fed up with the movies and wanted to refocus on singing. His comeback TV special at Christmastime 1968 signaled his return to live performing and resumption of the “hillbilly cat” identity with which his career began.

The next phase of Presley’s career began immediately when the Colonel set him up for a headline show at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. It was a difficult schedule — two shows a day, seven days a week. Taking a break now and then, he made occasional one-nighters, which were becoming more and more attractive to Presley.

As the letters show, during the entire time with Presley from 1956, Parker had juggled the negotiations for contracts, scheduling, song selection when it involved both the movies and RCA, marketing, promotion and other aspects of the career of someone of the caliber and celebrity of Presley. For all this, Colonel received up to a 50% draw for his various services. Presley was a great moneymaker, not just for himself and his manager, but for all those with whom Parker negotiated deals.

By the early ‘70s, Presley was showing signs of disintegration. His heavy use of drugs was certainly a factor. Wife Priscilla Presley had left him. Those who had seen him early in his Las Vegas stint were concerned upon returning later to note the decline in the spirit and fun of his performance. After a seven-year run, his Vegas days ended.

Although he indicated he wanted to resume touring, there were signs that Presley was reluctant to commit himself to performances that Colonel was poised to arrange. Presley was spending more and more time in Memphis with the cadre of friends who constantly surrounded him. Nicknamed "The Memphis Mafia," they enjoyed Presley’s company and the lifestyle they gained being with him.

Though Guralnick is not one to assign blame, he suggests that Presley’s friends were driving a wedge between Colonel and Presley. Rumors that were false but nevertheless were widely circulated were a source of distrust that was seeping into the long relationships the two had, for the most part, enjoyed.

In 1973, it seemed inevitable that a breakup with Colonel was coming because Presley neither accepted nor returned his calls and messages. A confrontation between Presley and Colonel finally addressed this issue, and Presley got to continue one-night bookings on a limited basis. Presley and Colonel remained friends, and Presley continued working almost until his death in 1977.

In considering all the evidence, Guralnick concludes that the unflattering persona of Colonel Parker that is held by many people is largely undeserved. His careful study of Colonel’s dealings with the stars he managed revealed to him no signs of neglect or exploitation. True, he had assumed a name and identity other than the one he was born with, but isn’t that what a lot of performers do? That’s show biz!