WASHINGTON — The U.S. Supreme Court postponed Friday deciding whether Louisiana should have one or two members of Congress elected from Black-majority voting districts.

The high court was slated to decide the case, which was argued in March, on Friday morning. The court instead stated it would soon issue a "supplemental briefing order" that would set forth the issues to be reargued in the next term.

The Louisiana case was the only one of 66 argued this term on which justices postponed making a decision.

Justice Clarence Thomas disagreed, saying he saw “no reason to avoid deciding the cases now."

“These cases also warrant immediate resolution because, due to our Janus-like election-law jurisprudence," states don’t know how to draw election maps that comply both with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Thomas wrote.

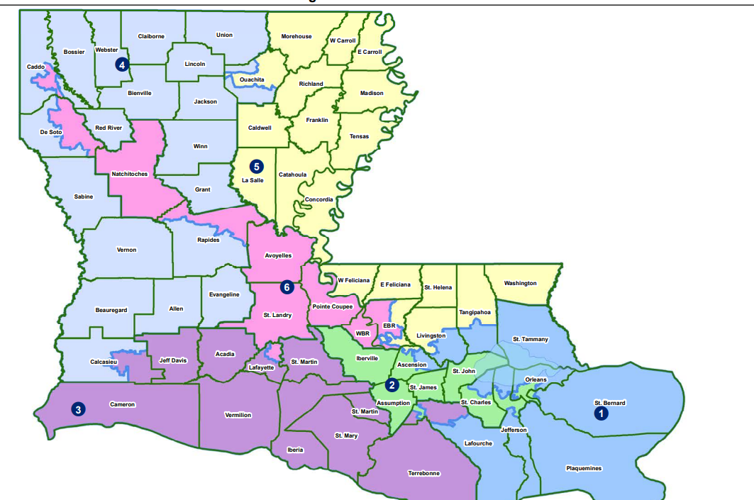

The delay likely means that Louisiana will keep the current configuration of the 6th Congressional District, which stretches between Baton Rouge and Shreveport, for another two-year term. The 2026 congressional party primary election is on April 18.

Louisiana asked the nine justices to explain how best to balance the often-conflicting requirements of the Voting Rights Act, which forbids watering down the number of voters who share the same race or language, and the Equal Protection Clause, which forbids using race as the primary factor to decide which voters can elect their representatives to the U.S. House.

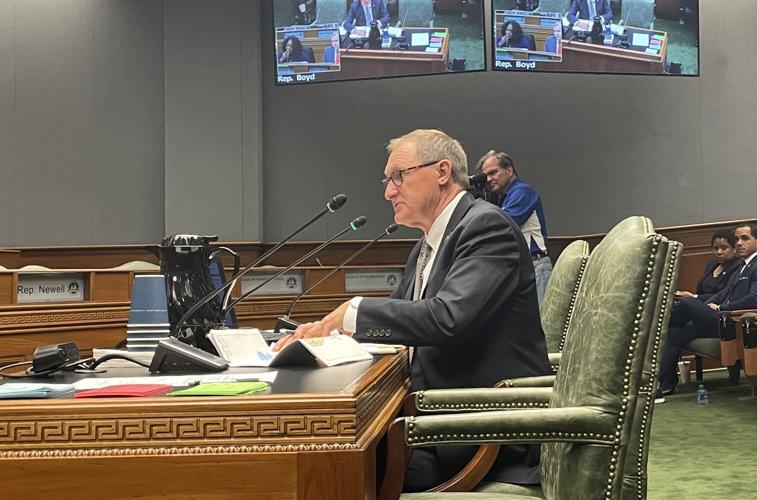

"There are two important issues on which, at least for now, the Court is not ready to articulate," U.S. Rep. Cleo Fields, the Baton Rouge Democrat elected last year in the redrawn 6th District, said minutes after the court postponed its decision.

“Although we hoped for a decision this term," Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill said in a statement, "we welcome a further opportunity to present argument to the Court regarding the states’ impossible task of complying with the Court’s voting precedents.”

Every 10 years, state legislatures are tasked with drawing the congressional districts of voters to comply with the latest U.S. Census count.

Initially, Louisiana legislators reupped the maps that spread Black voters among vast majorities of White voters, leading to five White Republicans and one Black Democrat in the House.

About a third of the state’s population now identifies as Black. And, since White majorities in Louisiana have never elected a Black candidate to Congress, a group of African American voters — who were called the Robinson litigants — challenged the Legislature’s maps.

They argued that simple math would dictate that two of the six congressional seats should be drawn to include enough minority voters to give Black candidates a fighting chance.

The state, however, argued that the Black population in Louisiana lived too far apart, making it difficult to meet other redistricting criteria, such as grouping like communities with similar political wants in a compact geographic area.

U.S. District Chief Judge Shelly D. Dick, of Baton Rouge, found that several alternative maps would indeed meet Voting Rights Act standards enough to create a second Black majority congressional district. A 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals panel agreed.

Confronted with the possibility of the federal courts drawing the new congressional map, Gov. Jeff Landry called a special session of the Legislature soon after his inauguration in January 2024.

The Republican supermajority Legislature decided to target Republican Garret Graves and his Baton Rouge-based 6th Congressional District. Graves had angered Landry and House Majority Leader Steve Scalise, R-Jefferson.

The result is a 6th district that links Black neighborhoods from Baton Rouge to Lafayette to Alexandria to Natchitoches to Shreveport. A Republican supermajority Legislature negated the previous maps and approved the new configuration for two Black majority districts and four White majority districts, which Landry in January 2024 signed into law.

Alternative maps would have significantly added Black voters to the north Louisiana-based districts that elected House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-Benton, and Rep. Julia Letlow, R-Start, a member of the House Appropriations Committee.

A dozen voters who describe themselves as non-African American filed a lawsuit in Monroe, where federal trial judges appointed by President Donald Trump preside. These "Callais litigants" argued that the new congressional districts that favored Black voters in two of the state’s six seats were drawn primarily to satisfy racial needs and thus were improperly gerrymandered under the Equal Protection Clause — that is, the voters primarily were sorted by race.

The state, which now had to flip sides, countered that, under the circumstances of needing a second minority-majority district to satisfy the Voting Rights Act, the primary motivation of choosing where that second Black majority would go was political — protecting Johnson and Letlow while targeting Graves.

The Robinson voters, who became intervenors under the new Callais case, argued that the new constituency was linked by a shared disinterest of the White congresspersons who rarely visited the minority communities along the Red River and did not champion their needs in Washington.

Two members of a three-member panel of 5th Circuit judges ruled the Legislature’s new congressional configuration was a racial gerrymander and ordered a May 2024 hearing to draw new maps. The third found that politics predominated the Legislature’s decision.

Louisiana asked the Supreme Court to stay the proceedings because the elections were so close that the Secretary of State could not properly stage the November 2024 congressional race without knowing what the districts would look like. The high court agreed, then accepted the case for arguments to sort how politics and race are to be considered in redistricting.

The election was held using the Legislature’s new maps and Fields, a Baton Rouge Democrat who was a state senator, won. He joined the House in January 2025. He has since voted with the Democrats, for the most part, in a House with a narrow GOP majority that often advances legislation by a single vote.

“The map adopted by the legislature was a product of bipartisan negotiation, judicial review, and compliance with federal law. It is not a racial gerrymander — it is a remedial measure responding to decades of underrepresentation,” Rep. Troy Carter, the New Orleans Democrat who represents the state’s other Black majority district, said Friday. “The ongoing legal challenges are deeply troubling, especially when they are driven by bad-faith arguments that twist the Equal Protection Clause into a weapon against equitable representation. Attempts to roll back the progress we’ve made are not about the Constitution, they're about power.”

Louisiana argued that legislators were put in an impossible predicament of being sued by one side under the Voting Rights Act if minority voting strength was diluted and sued by another for violating the Equal Protection clause if the redistricting had a racial component.

During arguments in March, the most conservative justices — Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch — questioned whether Dick’s ruling was “plainly wrong.”

The high court’s more liberal justices — Sonia Sotomayor, Ketanji Brown Jackson and Elena Kagan — questioned during arguments whether their colleagues should be considering Dick’s decision since the Callais litigants had not challenged her ruling and that the case before them is whether states needed “breathing room” when redistricting.

Of the three justices in the middle, Chief Justice John Roberts said during arguments that the 6th District configuration was not compact and ran like “a snake” through the state. Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked if there was a “logical endpoint” for the Voting Rights Act.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who grew up in Metairie, questioned the legislature’s redrafting based on a preliminary finding of lower courts.

“A fair and equitable congressional map has always been our North Star,” said Ashley Shelton, president and CEO of Power Coalition for Equity and Justice, a New Orleans-based grassroots group, and one of the intervenors in the case.

The “decision deferring the case does not shake our focus on that goal," she added.

ACLU National Legal Director Cecillia Wang said, “We will be back next term to once again defend the new map and the representation Black voters deserve.”