No buildings predating 1864 can be found in Alexandria.

Most of the structures were incinerated in the wake of the Union Army withdrawal on May 13, 1864. The few buildings that survived were leveled in subsequent years, leaving Kent Plantation House as the city's only intact centuries-old structure.

However, that isn't a contradiction about the city's pre-Civil War structures, because Kent House stood on what was considered outside of town at that time.

The Kent Planation House, the oldest standing structure in central Louisiana, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Though Kent House stands within the city's limits today, it stood well outside the city's 1864 limits. The house's owner signed an amnesty oath before the war pledging allegiance to the Union, which probably saved the structure from fire.

But that really wasn't Leon Bergeron's concern when he asked Curious Louisiana about the burning of Alexandria.

Who made the call?

"I want to know who gave the order to burn the city," the Alexandria resident said. "There's been some historical dispute about that question, and I'd like to find out the answer."

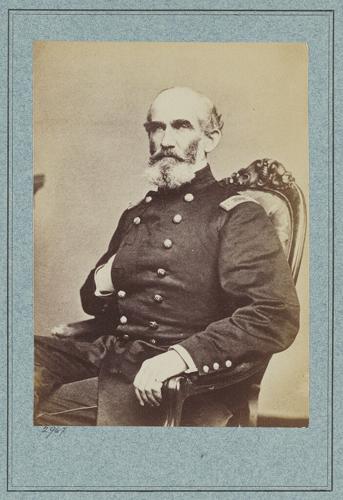

Some historians readily place responsibility on Gen. Nathaniel Banks, whose troops were occupying the city during the Union's Red River Campaign. Others say he gave no such order.

Before names can be named, it's important to know what led to the fire. That is, if there is a name.

Gen. Nathaniel Banks commanded the Union troops that occupied Alexandria during the Red River Campaign, which was designed to overtake Shreveport, which was capitol of Louisiana. The army was turned back at Mansfield and retreated back to Alexandria. Though Banks did not give the order, soldiers burned the city to the ground.

"Most of the historians' books I've read say Gen. Banks gave the order, but through my research, I believe that isn't true," historian and author Michael D. Wynne said. "Now, being the commanding officer, he ultimately bears responsibility. But he didn't give the order."

The fire was deliberate

Still, Wynne said, the fire was deliberate. He even emphasizes this rationale in the title of his 2022 book, "All Was Lost: The Deliberate Burning of Alexandria in 1864."

The unleashing of hell in Alexandria was the Union Army's final act in central Louisiana. "Hell" was the soldiers' words, and they had been through it after marching from New Orleans to Mansfield between March 10 and May 22, 1864.

Alexandria's bricked Third Street downtown as it appears today.

The Union's goals were to capture Shreveport, the state's capital at the time; destroy Gen. Richard Taylor's Confederate forces in west Louisiana; organize pro-Union state governments throughout the region; and most importantly, confiscate as much cotton as possible from plantations along the Red River.

Cotton was needed to supply the textile mills in the North, not to mention that the commanding general in charge had his sights on the White House.

"Banks was planning on running for president," Wynne said.

If Banks was the "hero" that supplied the cotton to keep Northern mills in business, the theory is that his campaign backers would skyrocket.

Plans go awry

Banks was given 20,000 troops to move from New Orleans to Alexandria, while Brigadier Gen. A.J. Smith was coming down from Vicksburg with 15,000 more.

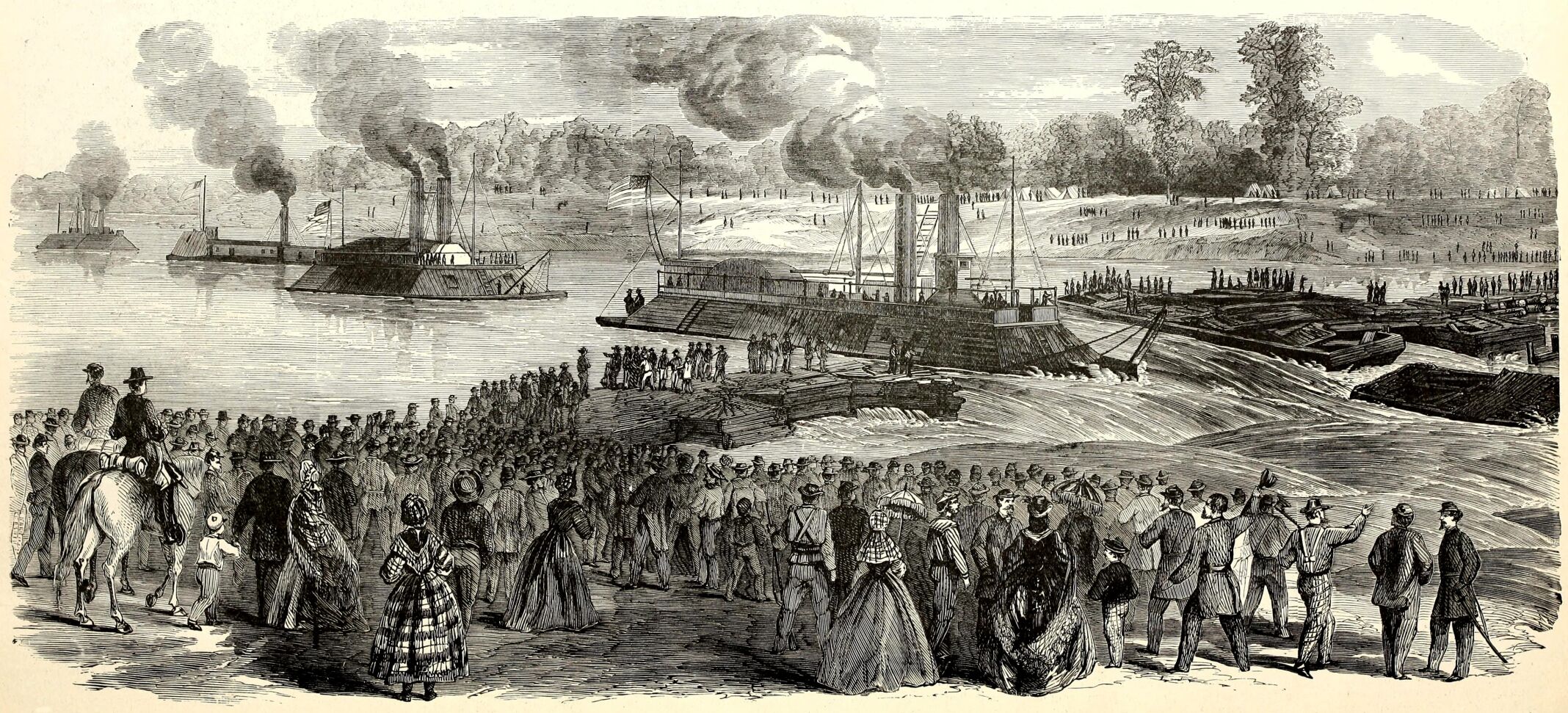

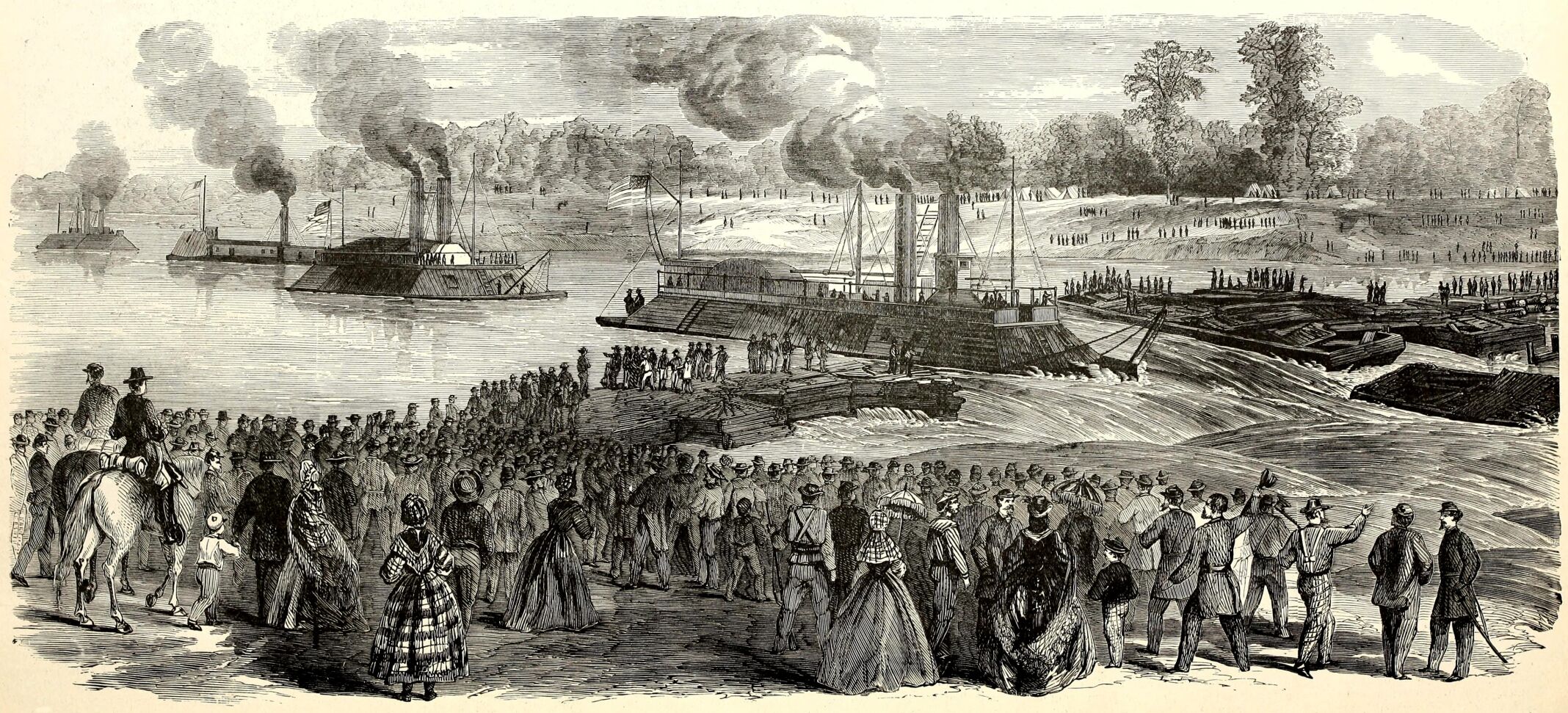

Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter led the Union fleet of ironclad gunboats up the Red River, then back down, where Col. Joseph Bailey had to construct a makeshift dam to make the water rise high enough to cross the seasonally low waters at the rapids in Alexandria.

Meanwhile, Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter was to lead a fleet of ironclad gunboats up the Red River in support of Banks' march into north Louisiana, the thought being that shutting off the Red River at Shreveport would isolate Texas from the Confederacy.

Banks' troops were in disarray throughout the trek and were turned back at Mansfield by Gen. Richard Taylor's smaller Confederate force. A battle at Pleasant Hill followed, and Banks retreated back to Alexandria, where the Red River's water table was seasonally low.

The Red River's rapids were prominent at Alexandria at this time, which were difficult for most water vessels to navigate. Low water crossing was doubly difficult for heavy ironclad boats, so Col. Joseph Bailey of Wisconsin was called in to create a makeshift dam that would raise the water level just enough for the boats to cross.

Construction of Bailey's Dam

Tensions were high during the building of the dam and even higher as the final boat scraped the river bottom after crossing.

Alexandria's downtown riverfront today. The Red River's famous rapids are no longer prominent since the lock and dam system has put in place for water control.

"The citizenry was concerned about the potential burning of the city," Wynne said. "They knew about Atlanta and other cities that had burnt from newspaper accounts, and the relationship between the people and the Union troops had never been very good. The soldiers had basically taken all of their food, chickens, cows and crops and were confiscating the cotton for the mills up in the North."

Not to mention that all of the trees had been chopped down on the Pineville side of the river, and the wooden buildings dismantled on Alexandria's side were used to build what historically has become known as Bailey's Dam.

An admirer of Gen. Sherman

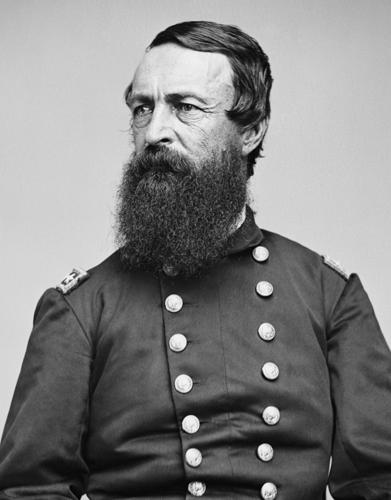

The proverbial nail in Alexandria's coffin was the presence of Smith, a close associate of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who was burning his way through Georgia at the time.

"He admired Sherman and was a Sherman wannabe," Wynne said of Smith.

Gen. A.J. Smith was an associate and admirer of Gen. William T. Sherman, who was burning his way through Georgia during the Civil War. Smith is said to be a proponent of the burning of Alexandria.

Wynne's research has taken him not only through history books but also court records, newspaper accounts and government documents. His findings led to an interesting discovery about Banks' character.

Sure, the general had political aspirations, but when it came to military duty, Banks believed in proper protocol.

"There was this delicate balance between political and military sides," Wynne said. "I would say he was 60% politician and 40% soldier, but he was still a proper military soldier, and he wanted to do things right. Lincoln was in the process of being reelected, and he knew the presidency would be wide open after that, because it was unlikely that Lincoln would run again."

Banks was decent

But that didn't mean Banks was bad.

"I have done extensive research on Banks' life," he said. "There were some real bad generals who used poor judgment and were morally questionable. But, Banks was a decent man. He got along with the people of Alexandria, but his troops didn't. And the people began hearing some of the soldiers talking about burning down the city."

Banks also heard the rumors, so he issued a letter on May 13, 1864, ordering a Col. Gooding to station 500 men to guard the city against destruction. The general was already on his way to New Orleans when the fire started.

St. Francis Xavier Cathedral in Alexandria. The church's priest stood in front of the original building at this same location in 1864, declaring that Union soldiers would have to kill him in order to burn the church. The soldiers backed off, and the church was spared.

"There's no written order by A.J. Smith, but there are accounts that he encouraged soldiers to start the fire," Wynne said. "They went from building to building starting fires."

Churches saved, destroyed

The priest at St. Francis Xavier Cathedral stood in front of the church, telling soldiers if they were going to burn the church, they would have to kill him first. The church was spared.

In the meantime, St. James Episcopal Church, which stood next to the river, was destroyed, but its silver sacristy set was saved and buried. That same set is used in St. James' current location today at the corner of Bolton Avenue and Murray Street.

This silver sacristy set was bought for the first St. James Episcopal Church building in Alexandria in 1844, which stood next to the Red River. When the Union soldiers burned the city during the Civil War in 1864, the set was hidden along with the vessels belonging to the Catholic church and later in the cistern of a member of the congregation. Fire destroyed the original St. James, but this set is still used at the church's current location on Bolton Avenue.

"Eighty-five percent of the buildings were destroyed," Wynne said. "And as the years passed, those that did survive were eventually torn down to make way for modern buildings."

As for Kent Plantation House, its owners had pledged allegiance to the Union before the war. The 1796 structure was moved two miles from its original location in 1964, preserved and is now open for tours.

"Historian Henry Robertson actually found the amnesty oath signed by the owner of Kent House in 1864," Wynne said. "That's probably what saved it."

A state historic marker outside the Kent Plantation House tells its story.

But saved from whom? Did Smith give the order to burn upon Banks' departure? That's the general consensus.

"It was probably a verbal order," Wynne said. "And there was no need for it. It was just done out of anger and hate, and for no other reason."