What was the Myra Clark Gaines case and is it true that it was the longest-running lawsuit in the history of the United States Supreme Court?

A dead father, a hidden will and a jailed husband: Meet Myra Clark Gaines, a 19th-century celebrity whose now-historic New Orleans legal battle turned her into a model for female persistence.

Gaines, who had a life filled with twists and turns regarding her parentage and inheritance, set the record for the longest-running civil lawsuit in American history. Her fight to win her birth father’s property lasted 57 years.

“To see that a woman was fighting for this, over 100 years ago, is just incredible,” said Katherine Jolliff Dunn, a curatorial cataloger with The Historic New Orleans Collection. “She continued and she did not stop. She really helped kind of set the path for women to really take a stand and not give up.”

Gaines was determined to receive her inheritance from her father, the wealthy New Orleans businessman and landowner Daniel Clark. She started litigation in 1834, helped along by her first husband. She would die in 1885, years before the case was finally settled in her favor in 1891, according to Dunn’s research.

“I think that she was very strong-willed,” Dunn said. “And once she knew that she was the rightful heir to this, she was not going to back down.

"Even after her first husband died and she got remarried, there were times that she was in there arguing for herself. She was not going to let anything get in her way. And I think that was her just wanting to prove that she means something and that this is hers.”

The child of a secret marriage

Gaines was born in New Orleans in the early 1800s to Clark and a Frenchwoman named Zulime Carrière. The two had been married secretly. After they split, Clark destroyed evidence of the relationship when he wanted to remarry, Dunn said.

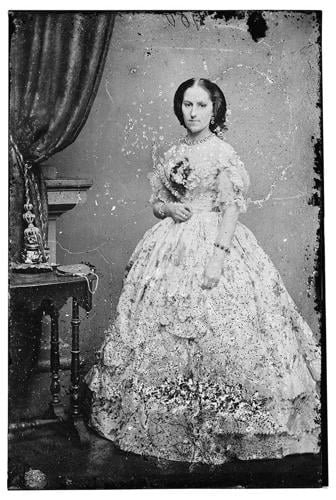

Myra Clark Gaines, photographed between 1855 and 1865.

Gaines was raised by friends of Clark and kept ignorant of her real parentage until around 1832, when she was going through her adoptive father’s papers. Clark’s 1811 will bequeathed his vast tracts of New Orleans land to his mother, administered by his business partners, extremely influential power brokers Beverly Chew and Richard Relf. The two would benefit heavily from the will, Dunn said, allowing them to receive much of his fortune and land.

Gaines found evidence of another will, made in 1813, that declared her his heir and left her all his property and fortune — estimated then at $35 million.

Dunn said Gaines unearthed evidence that the two business partners had destroyed this will for personal gain. As a newlywed, she filed the first lawsuit with the help of her husband, William Whitney, since women weren’t allowed to sue on their own.

Elizabeth Urban Alexander, author of “Notorious Woman: The Celebrated Case of Myra Clark Gaines,” talked about New Orleans’ response to her case.

“Those questions were not particularly well received by the New Orleans community, because if Myra Gaines was right, then the legal titles to a fairly large portion of New Orleans were being called into dispute,” Alexander said. “So the whole power structure of New Orleans gathered together to support the executives of Clark's will who were still alive, and to oppose this young couple.”

Sued and jailed for libel

Chew and Relf sued Whitney for libel, landing him in jail for a three-week stint. When Whitney died of yellow fever three years later, Gaines blamed the imprisonment for weakening him. After her first husband died, she remarried, and her second husband also supported her cause.

In 1858, the Louisiana Supreme Court finally nullified the 1811 will and upheld the validity of the 1813 will. But by this time, the original estate had been split up and sold off, with much of Clark’s former land now belonging to the city. Gaines then had to sue the city for her land, enduring decades more of legal troubles.

Alexander described Gaines as savvy, bucking social norms that expected women to stay quiet and unseen. Alexander said she’d dress fashionably — in one case showing up in court in black velvet, with diamonds in her hair and a silk hat with bird of paradise feathers. She’d have her second husband, a general, stand beside her in full uniform and introduce her before she’d talk.

“In other words, she's a picture of femininity while she's doing something that women are not supposed to do,” Alexander said. “She wanted to be part of her lawsuit, and she was.

"She argued her case by herself in court," Alexander said. "She was able to manipulate this sort of classification system of a woman as a lady, without completely violating it.”

Setting the trail for women

The final tally was 57 years in court, with Gaines' litigation pending in at least one court every single year, Alexander calculated. The lawsuit was heard 17 times before the U.S. Supreme Court and had over 70 court filings in various probate and district courts.

After the case was finally settled in Gaines’s favor, her heirs were awarded $923,788, but years of dragging litigation had incurred heavy legal fees, Dunn said. In the end, her heirs were left with just over $60,000 after these costs were paid.

“She didn't get to really reap the benefits,” Dunn said. “But the legacy of this, she really set the trail for women to be able to go on and have a much bigger role in their personal lives and society.”