Plans for a huge reservoir north of Baton Rouge to help keep the Amite River from flooding densely populated neighborhoods downstream have been sidelined by opposition from people who live in the countryside where it would be built.

Instead, the agency that revived the decades-old reservoir idea will focus on restoring curves in the Amite and keeping sediment out of the river, measures that could help scale down disasters like the widespread August 2016 flood, which damaged nearly 65,500 homes and thousands of businesses in East Baton Rouge, Livingston and Ascension parishes alone.

The agency, the Amite River Basin Commission, hasn't formally opposed the big reservoir in East Feliciana and St. Helena parishes. But it has now agreed to add the East Feliciana Parish government's latest objection to the idea in the commission's new master plan, which includes the reservoir.

Paul Sawyer, executive director of the commission, said the action means the agency will be "laser focused" on other projects that it has money and support for, two elements he called "essential ingredients." He said the reservoir idea has neither, even though research shows it would reduce flooding.

"What we have been saying even before this became a household topic in East Feliciana and St. Helena is that we can't do a project like this without the support and partnership of residents of East Feliciana and St. Helena," Sawyer said. "They have to be on board with this."

The commission will proceed with $100 million in Amite projects funded through the Louisiana Watershed Initiative, the state-run, federally funded program prompted by the 2016 flood, as well as with a plan to restore parts of the Amite to reduce downstream flooding.

It already has a deal in the works to buy more than 200 acres in St. Helena for the river restoration and hopes to finalize it soon.

The idea is to rehabilitate former gravel mining pits to restore natural curves along the middle and upper Amite and to find ways to prevent sediment from washing into the river. A straighter river with heavier sediment loads is believed to worsen flooding downstream.

Reservoir hits snag

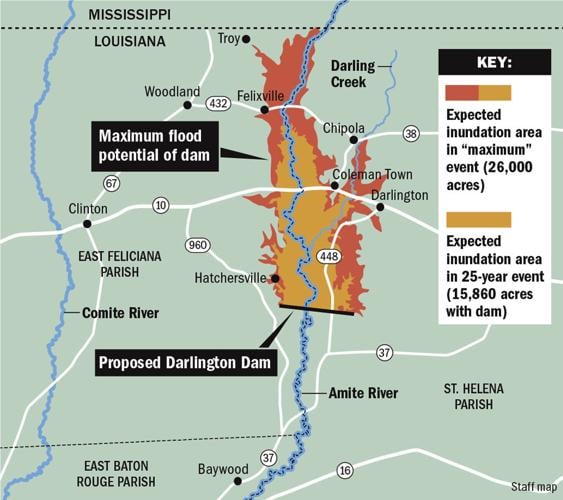

Gaining political momentum after the historic floods of 1983 — and then again in 2016 — the idea of a big reservoir has long been floated for the rural, hilly area north of Baton Rouge. The preferred location has been a section of the Amite River in East Feliciana and St. Helena just west of the community of Darlington, which gave the concept its name.

Repeated analyses by the state and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have shown that the rolling topography there can be used to store water, reducing flooding by several feet in more populated, low-lying areas downstream.

Building the storage area, however, would also mean permanently flooding tens of thousands of acres or greatly reducing their use, displacing people and potentially affecting businesses that rely on the land and the river.

Chrissie O'Quin, the East Feliciana Police Jury vice president, delivered the parish government's resolution of opposition to the reservoir to the Amite commission last month.

She said people don't want to be forced to give up their land, particularly for a project they fear may bring unwelcome changes to a rural area.

"They enjoy that peaceful life up there," she said.

Opponents have appeared at several meetings in recent months, including one at a church that drew more than 300 people.

O'Quin said she doesn't take the commission's acknowledgment of the parish's objection to a reservoir as an ironclad rejection of the idea. But she was pleased with the tenor at the commission's meeting Wednesday and with what was said by its chairman, John Clark, an Iberville Parish representative.

"I just want to remind everybody that East Feliciana Parish is part of the Amite River Basin," Clark said during the meeting, which was held in Livingston Parish. "They have a designated seat on our board, and they will always be represented here. Not to mention, East Feliciana Parish occupies a vast amount of river frontage along the Amite River compared to other parishes in the basin."

Despite the official opposition in East Feliciana, one landowner has offered, as an alternative with willing sellers, a few thousand acres for a smaller reservoir.

Sawyer said conversations with that landowner haven't gone forward.

Tried, and tried again

The reservoir has remained an alluring if difficult to realize idea for some because of its potential for flood reduction and economic impact.

After the devastating 1983 flood, the Corps suggested building the Darlington Reservoir along with the Comite River Diversion Canal. The canal, situated between Zachary and Baker and designed to reroute flood water to the Mississippi River, is now halfway built.

While the Comite Diversion has progressed in fits and starts over the past four decades, Darlington remained mired in controversy over its cost-effectiveness, its impact and questions about weak soil under the proposed dam site.

After the 2016 flood, the Corps took another look at the idea but shifted from a permanent reservoir in Darlington to a so-called "dry dam" with a temporary storage area of 26,000 acres. That dam would have held back water only during floods but still would have forced buyouts of several thousand homeowners and required limits on using land for forestry and gravel mining.

In 2023, faced with local opposition, the Corps ditched the $1.3 billion dam, citing the number of poor and minority households that would be displaced and concerns about weak soils causing the structure to catastrophically fail.

The Corps shifted to a $1 billion home elevation and flood-proofing program downriver, but that idea hasn't been welcomed by local officials because it won't stop flood water.

Newly revamped a few years ago by the Legislature, the Amite River commission, which had faced years of criticism over the slow pace of the Comite Diversion, was tasked with creating a long-range plan.

Finished this spring, it included a handful of reservoir concepts. Commission officials say they were mandated to look at the ideas despite long-standing opposition.

O'Quin, the East Feliciana police juror, recalled a recent conversation with someone who helped his parents fight the Darlington Reservoir in the '80s and '90s and has fought the more recent dam proposals.

"Are my children going to have to do this, too?" O'Quin said the man asked her.

"And my answer was, 'Probably,'" she said.